Yeah, we got one, too.

Drinking was my friend: How I talked to my daughter about my alcoholism

This article was originally posted on the Today Show website.

When my older daughter, Fifer, entered high school, I introduced the concept of Amnesty Day. On the last day of every month, she got to tell me anything she’d done that wasn’t what she was supposed to do—and not get in any trouble for it. We talked through what choices she could have made differently, but on that day only, she didn’t get guilted, or yelled at, or grounded for not following the rules.

When Fifer’s confessions were about her own behavior and choices, that worked out well in terms of opening the lines of communication. As she approached legal drinking age, however, I needed to be able to discuss alcohol with her in a way that would prevent her from getting sucked into the void of her newfound freedom. How could I do that without relating my own battles, which eventually led to my becoming sober?

That was not something I could hide, like we couldn’t hide the fact that our younger daughter is adopted. Bodhi is from Taiwan; my wife and I are white. We never tried to figure out when would be the right time to tell her. She’s just always known, just as Fifer has always known I am a recovering alcoholic. Dad doesn’t drink. There must be a story there.

There were a lot of stories there. There were nights that didn’t end without my getting cut off at a restaurant, alienating everyone I was out to dinner with, and lying down to hiccup in the gutter for an hour. In those days, I wrote as many poems as I finished off bottles of scotch; I had to have the former to justify the latter. I got the shakes; I had hallucinations; I was not headed for a long life.

In recovery, you’re not supposed to tell these stories in a way that makes them sound romantic. With Fifer, it was doubly important not to make my escapades sound appealing. If I told her what I did when I was her age, would that give her permission to do the same? There was a lot riding on our not misunderstanding this fine line.

As I searched for a way to communicate my history, I came upon the journal I kept during the early days of my sobriety.

I didn’t write a lot in it (and I can write a lot when I want to!). It was actually just a series of 41 different answers to the same question, one that my therapist, Gretchen, had posed to me:

“Why can’t you stop drinking?”

The first time she asked me that, my response was “Because drinking is my friend.”

Gretchen didn’t like that answer. She challenged me to abstain from alcohol for a month, and to use that time to record all the reasons I wanted to take a drink, even as I knew drinking was not working in my favor.

I started with some pretty mundane motivations. I want to drink . . .

. . . because I’m in a bar.

. . . because the best man from my wedding is coming to visit.

. . . because I need a day off.

These soon graduated to more serious appraisals, however, about what wasn’t working in my life:

. . . because work isn’t going well and I may have to leave eventually.

. . . because I’m so frustrated.

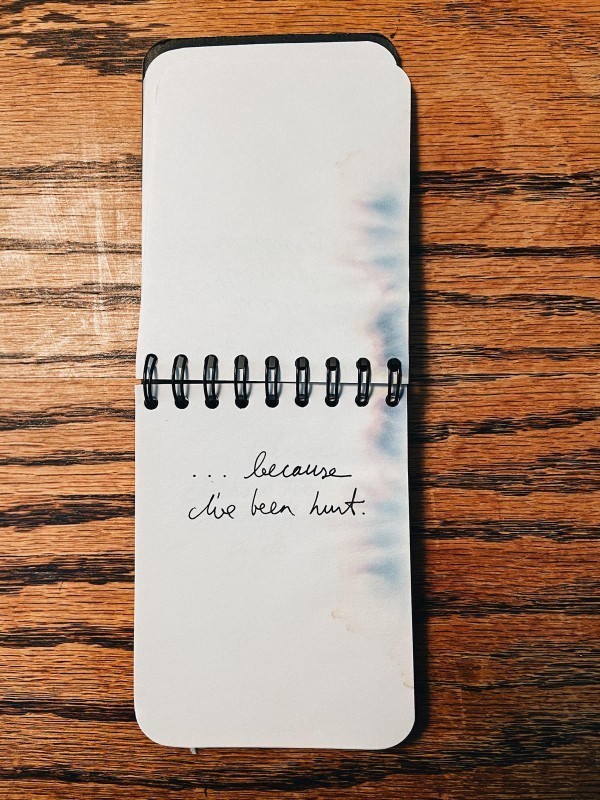

. . . because I’ve been hurt.

I wrote one reason per day, and as I dug deeper, I uncovered what had been driving me all along.

. . . because no one has any space for me.

. . . because I don’t have any space for me.

. . . because I don’t know who I’ll be if I stop.

Forty-one days later, I closed the journal, and I have been sober ever since. I’m not saying that my lack of self-love blossomed into a reliable self-esteem overnight. But my life did start trending up. The things I learned yesterday were still there today. I was building on something, instead of waking up to find it all wiped away while I stood in a hole of my own making.

When I showed this journal to Fifer, it was in the context of Amnesty Day. In doing so, I realized I was seeking amnesty from her. Not healing in the sense that my past never happened, but healing in the sense that it did happen. It could be released from the dark corners of my mind.

In an unexpected turn of events, her witnessing me allowed me to witness her. Rather than feeling as if she had license to misbehave, she seemed to trust me more. Now when I counseled her on how not to get taken advantage of at a house party or be part of some horrific accident in college, I didn’t seem as much a hypocrite as a mentor.

I know I can’t save her from making the mistakes that are hers to make. Everyone has their own road. But she believed me when I told her that I wanted her to write the next chapters of her life with more light, more self-possession, and more inner peace than I ever had. She heard me say a prayer that she keep herself safe by loving herself. And that is a prayer that I have come to have faith in.

Leave a Reply