I need to tell you something I’m not very proud of. I fear it will reflect badly on me but maybe the understanding I was granted will partly offset matters.

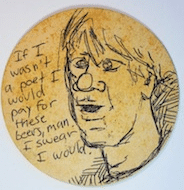

While in Prague, I hung out with a group of expats, sleeping on their couches and drinking other people’s warm, unattended beers in outdoor restaurants. This isn’t the bad part. Ken Nash borrowed a coaster one night in a pub and handed it back with a well-drawn caricature of me.

The caption read, “If I wasn’t a poet I would pay for these beers, man. I swear I would.” Ken later became a famous illustrator. A lot of the crew in those days went on to become professors, or novelists whose books were turned into movies, but this was before publications and careers were the most important thing. The hierarchy of the streets then was all about one-liners; your cool was based on how present you were.

You might think this is pretentious, but I remember the time a friend of mine called me up crying. What was wrong? I asked her.

“I just wrote a poem,” she said.

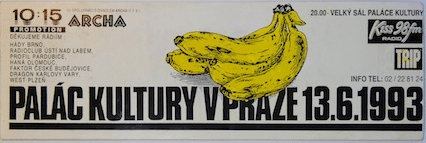

She was not embarrassed; she was overwhelmed by emotion. We were living for creativity in a city where every day dawned from a different angle. It is difficult to describe the atmosphere of Prague in the early 1990s. Some historians compared it to San Francisco in the 1960s or Paris in the 1920s. I’m not qualified to judge cultural moments like that, but anyone could feel how electric the atmosphere was as the city shed decades of communism. The liberated country elected an absurdist playwright, Václav Havel, to be its first president. Havel brought in the costume designer from the movie Amadeus to design the police uniforms. Shit like that.

Havel had even named the nonviolent political movement that resulted in a Western-style democracy in Czechoslovakia, the Velvet Revolution, after Lou Reed’s band, the Velvet Underground. The band itself reformed after twenty years and I got to see them perform a concert in the Palace of Culture. Americans were welcomed as symbols of intellectual freedom, although there wasn’t much in the way of employment for many of us.

I didn’t require much. I had gotten used to eating oatmeal with brown sugar, fruit, tuna with pasta and parmesan, and repeat. I was thirty-five pounds lighter in those days, although that could have been the cigarettes.

I had saved up a shoebox full of cash working as a waiter in the States, but it had now been depleted. I couldn’t ask my parents for money. They wanted me to settle down, get a career going. They didn’t want to sponsor me any longer. Although, as a fellow expat, Jennifer, pointed out, they did send me $200 and a scarf when they heard where I was going. It was going to be cold in Central Europe.

Here comes the part that makes me wince. To make ends meet, I stole books. Dozens of them, from the two English-language bookstores. And then I either returned them to the original store for cash or sold them somewhere else at half-price and put the proceeds toward my one meal of the day, timed for about 3pm.

The shopkeepers didn’t catch on, even though books like John Berryman’s Collected Poems were 347 pages in the Faber & Faber edition—not a perfect fit under the shirt, but it retailed for $32. That went a long way in a second-world economy, and No, I’m sorry, I don’t have the receipt. . . .

It’s pretty ironic that a starving artist would choose a starving-artist business from which to pull off his heists. Maybe a bookstore is the only place I felt comfortable enough to do something like that. Or maybe that’s just where I was most often. It wasn’t about being a scofflaw. I didn’t do it for thrills. At the time, I thought I was just trying to survive.

Stealing is wrong. It occurred to me several years later, standing next to my smashed-up rental car in San Francisco, where thieves had taken several suitcases, some of which were filled with expensive presentation electronics, that I was looking at karma. Among the missing items was a box of thirty copies of the books I had written. I shuddered to think what dumpster they had ended up in. Karma may not be that tit-for-tat, but it could be close.

I just wanted to be a writer so badly, and the inspiration I found overseas was unmatched in my previous experience. Writing was the main focus of every day. Based on which side of your family, or which side of your psyche, you are drawing from in the moment, this single-mindedness is either noble or indulgent; it shows either romantic impracticality or strength of commitment. I have heard it all.

They say sometimes to get along you have to beg, borrow, or steal. Or is it beg, borrow, and steal? There wasn’t anybody left to borrow from, and my conscience had finally gotten the better of me, so I was left the first option to continue my writing mission. I had to beg from someone who understood though.

I wrote a letter to my great-uncle Manny. There is a lot I could say about my great-uncle. I once dropped his birthday cake after having been given the honor of carrying it out to him during the singing, and all he did was laugh and convince me the screwed-up icing made for a better story this way. He believed in reincarnation, which was pretty unusual for a Jew born in 1910. At times, he would do things that fit his type, like drive a lime-green Cadillac or eat hard-boiled eggs with mayonnaise. But then he would come out with Zen-like sayings that you were never sure if even he understood.

I remember at one cocktail party, I was talking to a famous surgeon, or, rather, he was talking to me. “Stuart, all that matters in life is whether you think the glass is half full or half empty. Watch this”—and here, he grabbed Manny’s elbow. “Manny, is this glass half full or half empty?”

“That’s not my glass,” Manny responded.

See, like that! Did he mean that, or was that coincidentally mystical?…

I asked Manny for a thousand dollars, and he came through as a patron of sorts. He was straight with me; he told me I was now living the “life of Riley,” meaning my adventures were being paid for by someone else. But he also praised me for meeting challenges that would have been too much for him.

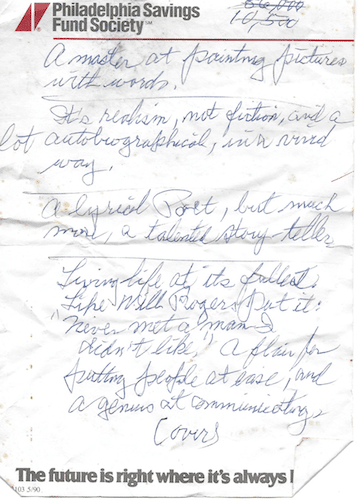

It was a very balanced portrait. He liked my poems and wrote me a letter on Philadelphia Savings Fund Society notepaper telling me his favorite aspects of them. He said I was a master at painting pictures with words. He said I reminded him of Will Rogers in that I “never met a man I didn’t like.” Writing did bring out the best in me.

It was a very balanced portrait. He liked my poems and wrote me a letter on Philadelphia Savings Fund Society notepaper telling me his favorite aspects of them. He said I was a master at painting pictures with words. He said I reminded him of Will Rogers in that I “never met a man I didn’t like.” Writing did bring out the best in me.

He never told me to come home. He never mentioned the money until the end of the letter, when he wrote, “P.S. Check enclosed.”

I read his letter again looking for some judgment. He shared a few details from his life, casting everything in a positive light. When he wished me good luck that was the entire sentence. Rereading brought me only courage, all the way through to the end. “P.S. Check enclosed.”