This excerpt from my upcoming memoir, Amnesty Day, was originally published in Hippocampus Magazine.

I was among the first wave of fathers to do at least 50 percent of the childcare. I can’t prove that, of course, except by telling you how out of place I was made to feel.

If your mom and I took you to the doctor, the nurses wouldn’t even look at me. They just kept asking Bonnie, Is the car seat facing the rear? How much of the bottle does she take? How many ounces? These questions were of real concern to us because you were always underweight (or “puny,” as we had taken to calling you).

The only problem was, I was the one with the answers.

“Did she eat anything today?”

“Yes,” I ventriloquize through my wife, “she had two four-ounce jars, one of peaches and the other of mixed garden vegetables.”

One time when I took you to the emergency room, the admitting nurse actually said to me, “Oh… Daddy didn’t know what else to do!”

I was both worried and relieved when you had a temperature of 104 degrees. You see, I’m not an idiot! Now, don’t take me too literally on that; in those days, when the first star appeared in the sky, my first wish was always for your health. Everything else was relegated to wishes two, three, and four.

I started calling it the Mommy Conspiracy. Mothers came up to me in the supermarket to point out that there was a harness in the front part of the shopping cart where you should be strapped in, when you would be in the main carriage, eating escarole. Does this happen to women, too? I don’t know. I just know that I was told you were going to need your hands washed after we were finished playing at the park—I was actually told that dirt was dirty—or that your foot was dragging behind the wheel of the stroller where you always put it. You loved to feel the road.

Around this time, they started showing the first commercials aimed at stay-at-home fathers. Like the one where a dad is vacuuming while giving two very young children a piggyback ride at the same time: I’ll buy it! I know we already have a vacuum. They’re targeting me, can’t you see!

What I’m describing is almost commonplace now, but in those days I couldn’t win. If we were playing tag at the outdoor shopping mall on Saturday, they would tell you, “I can see somebody’s going to be a real daddy’s girl!” If they saw us at 1:45 p.m. on a Tuesday, it was like, I wonder what he does for a living.

I was a waiter. Well, really, I was a writer. I was sensitive to the criticism, of course, that’s why some of it stuck. It was a better time for your mother than it was for me: She was getting her doctorate in psychology and was surrounded by passionate people. I was writing a novel about suicide, which might tell you much of what you need to know. But then we had you. And the arc of my life that had been trending inexorably down suddenly banked upwards with the same unmistakable force.

Your mom would let me sleep until she left for her graduate school classes, and then I would be on: feeding you, finding ways to entertain you, saying no to candy, often, or changing your diaper for a third time during your pre-nap dramatics.

Bonnie did certain things better than I did. She made up the best nicknames, and little songs like when you were just getting your spatial relations down. Stack ‘em up, stack ‘em up, stack ‘em up cups, she would sing, as you made your first pyramids of plastic. She could soothe you far more easily when you were teething and I got frustrated.

“She’s just a little girl,” she would say.

In truth, we were glad there were two of us, for the massive amount of work a kid is. I just wanted the credit I was due. I was the one who took you to every single playground in the county where we lived north of San Francisco. They each had a nickname, like Pinchy Fingers, for the time you got your hand caught in the gate. I was the one who distracted you from your pain after falling off a swing from a decent height; I walked on the balance beam and pretended to trip, throwing myself headfirst into the sand a dozen times until you stopped crying.

I’m almost finished complaining. The worst of the Mommy Conspiracy came at Gymboree. If you don’t remember precisely what that was, it was not just a clothing store. Beyond the outfits and light-up shoes was a giant playroom filled with brightly painted jungle gyms and learning toys that lay strewn on multicolored mats.

The first time you laid eyes on that, the look on your face changed. All right! your gleaming expression seemed to say. Now we can get down to some serious playing!

It was very hard to resist you when you had just glimpsed a new possibility. There would have been reasons to leave. Sitting in a circle and singing songs with strangers was not up my alley then (or, really, now). Opening up to that situation was made much harder, however, while I was also being observed with such scrutiny. One day a mother whispered fiercely to me, “She can’t see you!” when you kids were playing under the parachute. You were an independent child. You didn’t have to see me all the time. In fact, it was better if you didn’t sometimes. Then we would have a little reunion, and in the meantime your confidence would have grown at the same pace as your puny body.

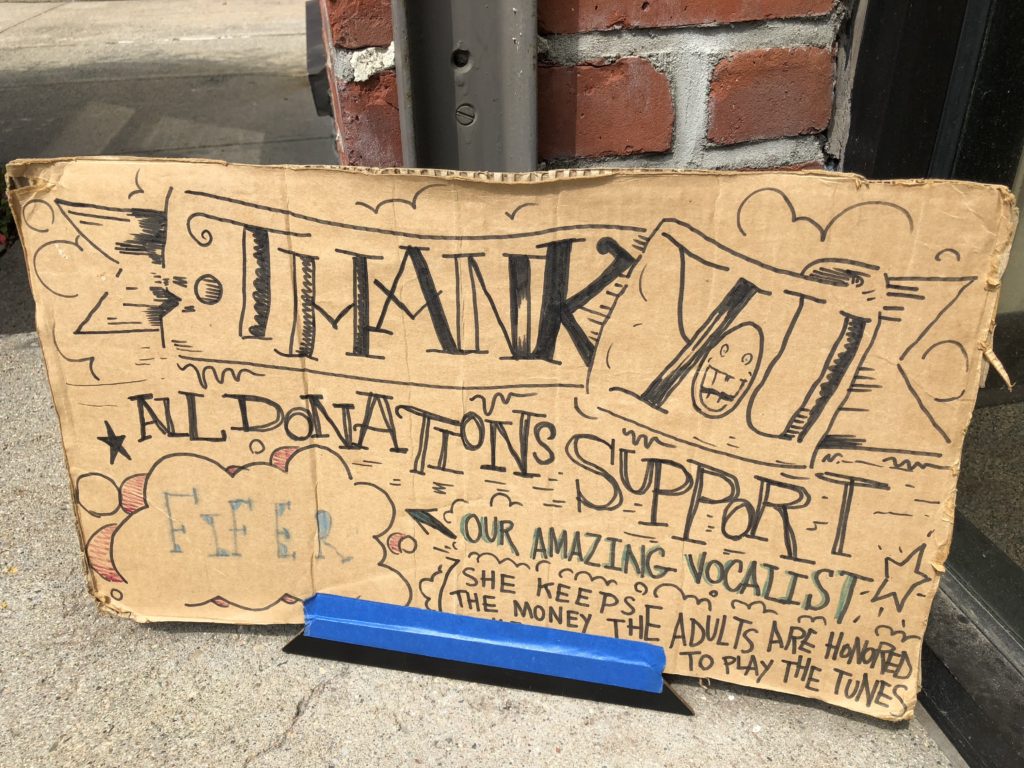

This was why we had to find our fun in unconventional places. We would pile into my leased navy blue VW Jetta and let the day direct us. Our demands were not high. The pizza place had a sticker machine, and for two quarters you might pull out Strawberry Shortcake or a SpongeBob-themed $2,000 bill. We might buy a fresh pack of baseball cards and go through them one by one or visit the farmers’ market and sit in the audience, watching Twee-Twee the clown make balloon animals, while the sunshine poured down on us.

But the best thing of all was a bouncing ball. No bigger than a quarter, if it was flat, a good bouncing ball could always surprise you with the way it ricocheted off walls and rocks and trees and across streets—Don’t you dare go get that!—and up stairs and down escalators, animating every scene it entered.

The farmers’ market was held in the parking lot of the Civic Center, which included the Marin County Superior Court. You wanted to take your bouncing ball in there one day. Except Daddy doesn’t do courthouses.

You can’t tell a three-year-old about all the arrests and infractions that led to a well-attended trial in college—which, if I had been convicted, I would also have been expelled from school—such was the nature of town/gown relations. My brushes with the law stopped about the time I quit doing drugs, and then you were born, and I quit drinking, too.

Some part of me still didn’t feel free, though. We had a little stand-off outside of the Civic Center. You were never one to take ‘no’ for an answer even when there was a good reason, let alone when all I could come up with was a fumbling, half-conscious reason.

Of course you won that battle. I was pretty sure I was safe with you. You charmed security guards and harried lawyers and struggling souls weighed down by multiple misdemeanors. Pretty much everybody stopped to give you your ball back.

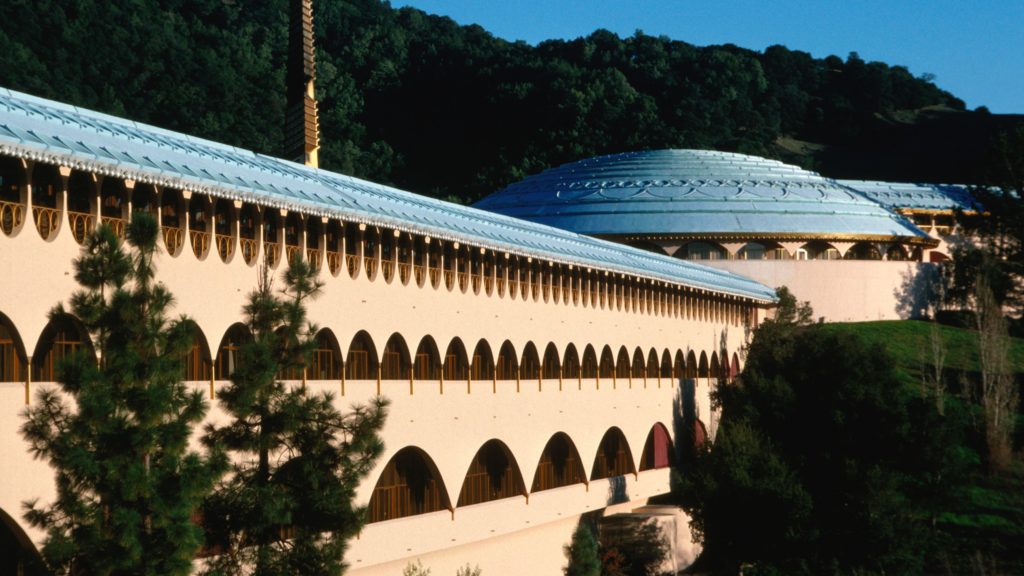

The building was gorgeous. I should have gone in there earlier. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, it nestled into the low-slung terrain like a stucco aqueduct. The earth-toned colors blended into the chaparral and oak woodlands, and it had fountains both inside and out.

You bounced your ball into an operating fountain. It was an apotheosis of enjoyment for you, and only a minor hassle for me to take off my shoes, roll up my pants, and wade in to retrieve it. You bounced it in again and again, your head thrown back just before laughter, while I decided that if this was what I was going down for now, I would be just fine with that.

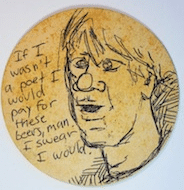

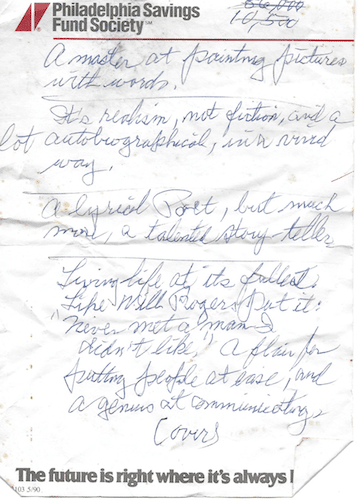

It was a very balanced portrait. He liked my poems and wrote me a letter on Philadelphia Savings Fund Society notepaper telling me his favorite aspects of them. He said I was a master at painting pictures with words. He said I reminded him of Will Rogers in that I “never met a man I didn’t like.” Writing did bring out the best in me.

It was a very balanced portrait. He liked my poems and wrote me a letter on Philadelphia Savings Fund Society notepaper telling me his favorite aspects of them. He said I was a master at painting pictures with words. He said I reminded him of Will Rogers in that I “never met a man I didn’t like.” Writing did bring out the best in me.