(This is a lightly edited version of a speech I gave at the Pennwriters Conference Luncheon several years back.)

My first book was published by Penguin in 2013. It was nice to get that monkey off my back. I always dreamed of being a published author, from my childhood when books spoke with the clearest voices I heard anywhere. I wanted to participate with that. I was also tired of getting that question; you know the one, “Oh, so you’re a writer…are you published?”

I still have a few monkeys on my back, so don’t get too jealous. Besides, when I got published, it wasn’t like I joined some secret club. You’ve likely heard the tales: one book pays for the other six, they don’t put any money into promotion, and so forth. While I relished that seal of approval on the spine, and leaning on their expertise as mine grew, I was the one who set up all twenty spots on my book tour that first year.

On the road, I’ve had all kinds of experiences. I’ve presented to 300 people, and I’ve presented to zero people. Actually, I didn’t present that night, I packed up all of my gear, and when the lone straggler came in to ask if this was where the reading was, I smiled at her broadly: “Nope.” I’ve gotten five star reviews which said, “Thank you for existing.” And I’ve gotten one star reviews saying my writing was “as dry as sawdust.”

For the most part, it’s been great. I’ve now completed 70 tour dates throughout North America in the past three-plus years. But no matter how exciting life post-publication has been, it has never gotten better than those champion writing sessions where I was achieving the height of my flight. When someone says, “Your books are so original; I have learned more from you than anyone else” — I am happy, of course — but it is like I am hearing about a trip they’ve taken when I got left home.

Nothing will ever beat those rare nights when I knew I nailed it. When I had prepared for a writing session, and executed, while welcoming the unexpected. And then went to go smoke a cigar in the heart of Providence. I might have been thinking about the people who inspired me, but sitting there it was just me, myself, and I.

So my point is that we need to take writing and separate it from publishing. I’ve published three books on writing, but I also have an unpublished novel and an unproduced play. What writing has done for me exists outside of the experience of being published, and far exceeds it in value.

When I work with writers as an independent editor they sometimes put too much emphasis on publishing like that will determine the worth of the exercise. Other parallels could be sought here. I’ve run two marathons — should I not have done them because no one later called me to compete at the Olympic trials? (Maybe if they wanted someone who ran it in twice the time trials mark?)

There are things we do because we are called to do them, and that is what we can control. We can’t control fate. In Buddhist iconography the person is represented by a little wheel and the universe by a big wheel; when their teeth link up and they turn together, that is when you get your “15 minutes of fame” as Andy Warhol might have said… And then the big Wheel of Fortune spins on, and it may be a long time until you are linked up again.

So what are we supposed to do with all that lonely empty wheel space in the meantime? Live in the Glory Days? Feel like an impostor? Worry about the future? Try to chase the market and write something that meets current popular trends?

While we are waiting for the little wheel to intersect with the big wheel, we get distracted from what is really important in our own development. Like, what is the best thing I could be writing right now? What have I learned so far about writing that can help me reach my next goal? How much time can I find to pursue my passion of writing? How can I let that passion change me? What kind of excuses do I need to find for the people in my life to explain what I am doing?

How can I commit to the lifelong process of finding myself as a writer? What trips do I need to take? What people do I need to meet? What research do I need to do? What music do I need to listen to? What kind of community do I need to join, or create?

Earlier in the cigar story I referenced those people who inspired me in my current project. Some are editors, some are beta readers. Some are just people who make sense every time they speak. I call them my team, and put their names in the Acknowledgments section of the new book. Some of them are surprised. “What am I doing here?” they ask. “It’s a long story…” I say.

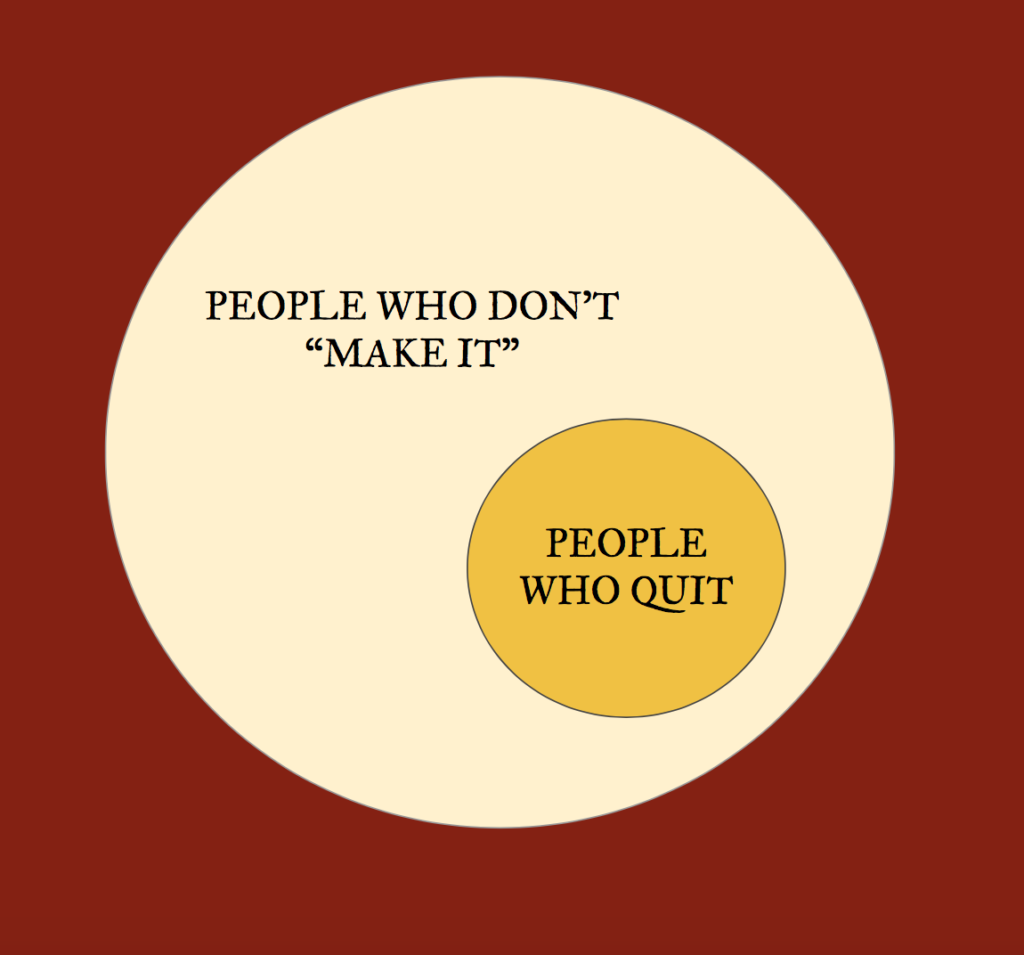

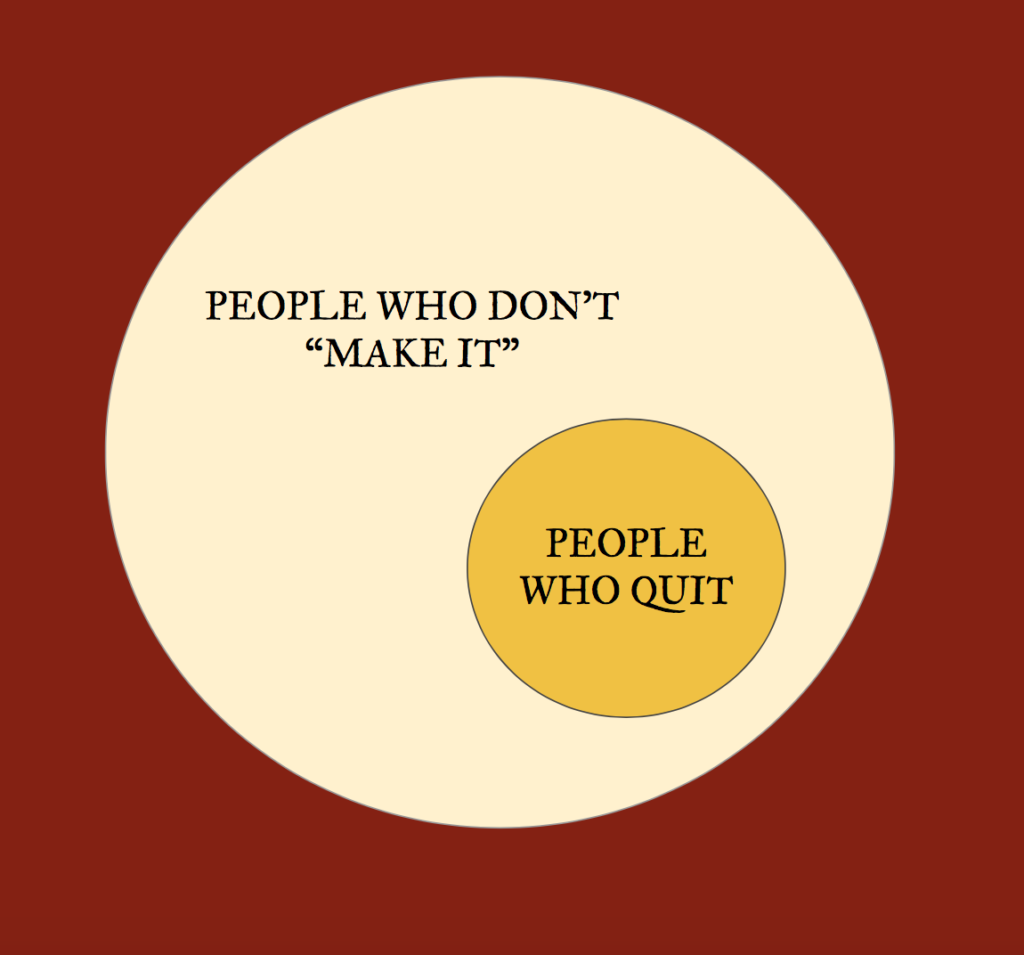

Basically, you’re there because you helped me not quit. That’s the best thing you could have done for me. I once drew this Venn diagram which shows how, of the people who don’t “make it,” all of the people who quit are contained completely in there.

And now, an excerpt from one of my books. This is from the section, “Why Some People Don’t Finish.”

I think that a lot of the reasons people don’t finish is because they don’t have a structured process to know what they need to be working on, when. That’s a pretty innocent way of getting lost that hopefully this book has helped a little with.

Some people don’t finish because they can’t keep the publication wolves at bay. Daydreams about acceptance, and the converse, anxiety attacks about rejection, and not going to help you finish. Sometimes, this pressure from the outside world gets too intense, or sometimes people can’t bring themselves to put themselves out there as the author of this book. They may have what are called hidden, related commitments—something just as strong or stronger that is working against them being a successful, published author.

Whether you want to get really deep about it, or just say, “I can’t seem to find the time…” there is one thing I want to say that will seem pretty obvious. The people who quit, can’t make it. Finishing requires tenacity. Taking something all the way to the end always looks kind of insane. Of course, it won’t feel insane. It will feel indescribably satisfying.

Instinctively, we know that every draft is different. In the first draft, we can’t really be held responsible for the exact quality of what we produce; we just got here, ourselves. We are just trying to cover the ground. In the second draft, we might be learning the ropes a bit more. We can say what the better stuff is that we are trying to bring up another level. By the third draft, we are ready to polish, decide, and hopefully finish something.

Instinctively, we know that every draft is different. In the first draft, we can’t really be held responsible for the exact quality of what we produce; we just got here, ourselves. We are just trying to cover the ground. In the second draft, we might be learning the ropes a bit more. We can say what the better stuff is that we are trying to bring up another level. By the third draft, we are ready to polish, decide, and hopefully finish something.