Independent editing is a mentorship industry. There is little to no targeted training and an absence of concise, reputable-seeming resources available. Enter: the Independent Editor Podcast. With episodes dropping every other Wednesday, starting October 27, it is our aim to serve as a support for aspiring editors who may be experiencing a crisis of confidence, a community for those that toil alone, and a resource containing detailed and practical direction. Below, we present to you a sampling of what’s coming:

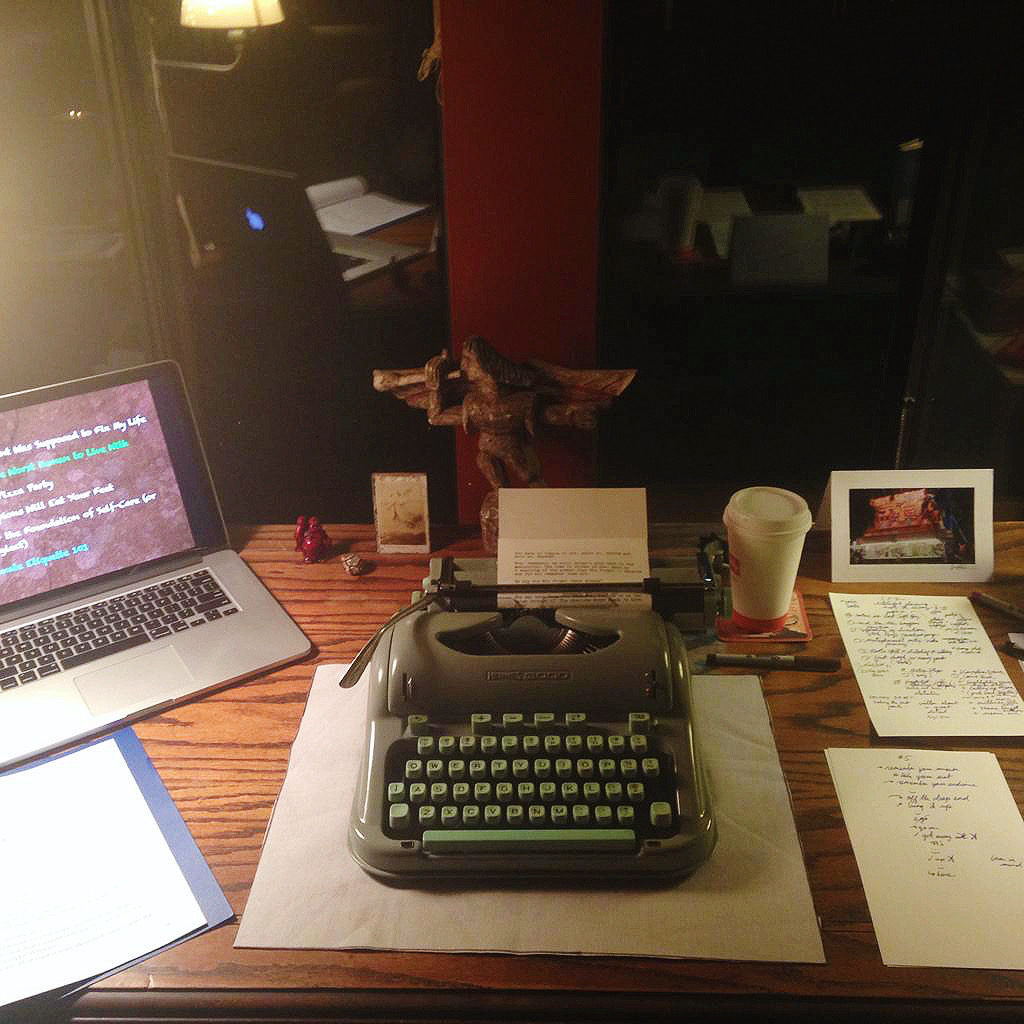

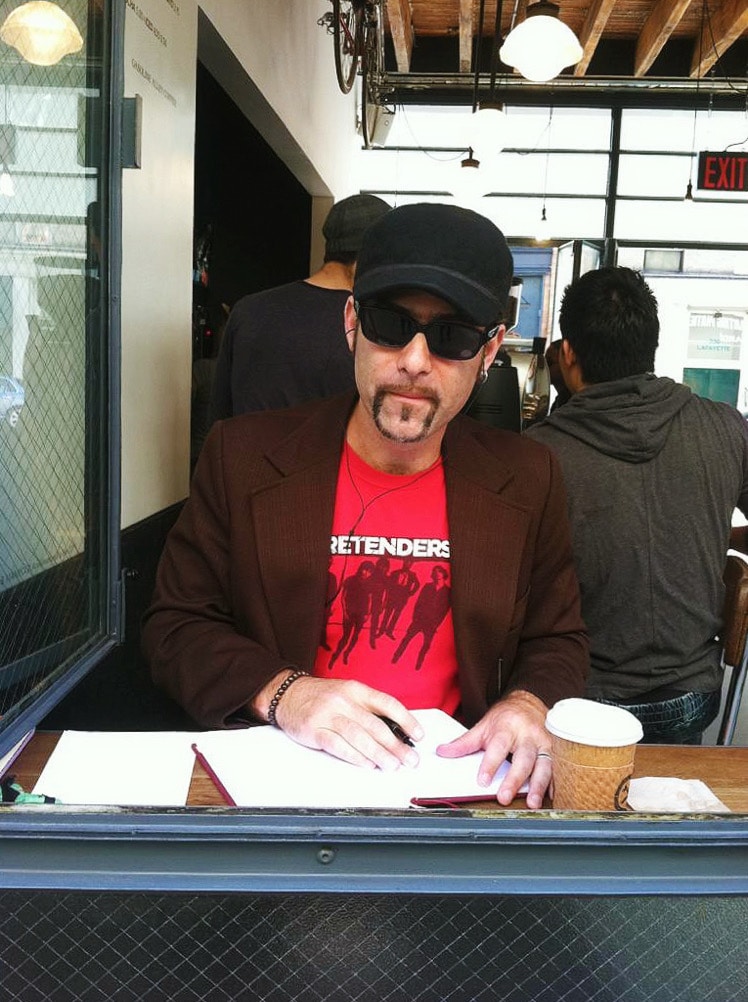

Why should you care what we say? To kick things off, we talk about how we each found our way to the industry—and to each other; Stuart tells us how he purposefully waded in while Madison explains the fortuitous manner in which she found herself shoved into the deep end. The stark difference in our paths (and experience levels, with Stuart 20+ years into this whole thing and Madison just three) means we’re able to speak to independent editors across the spectrum. Here, we also get into the changes in traditional publishing which allowed for the flourishing of the independent editing industry.

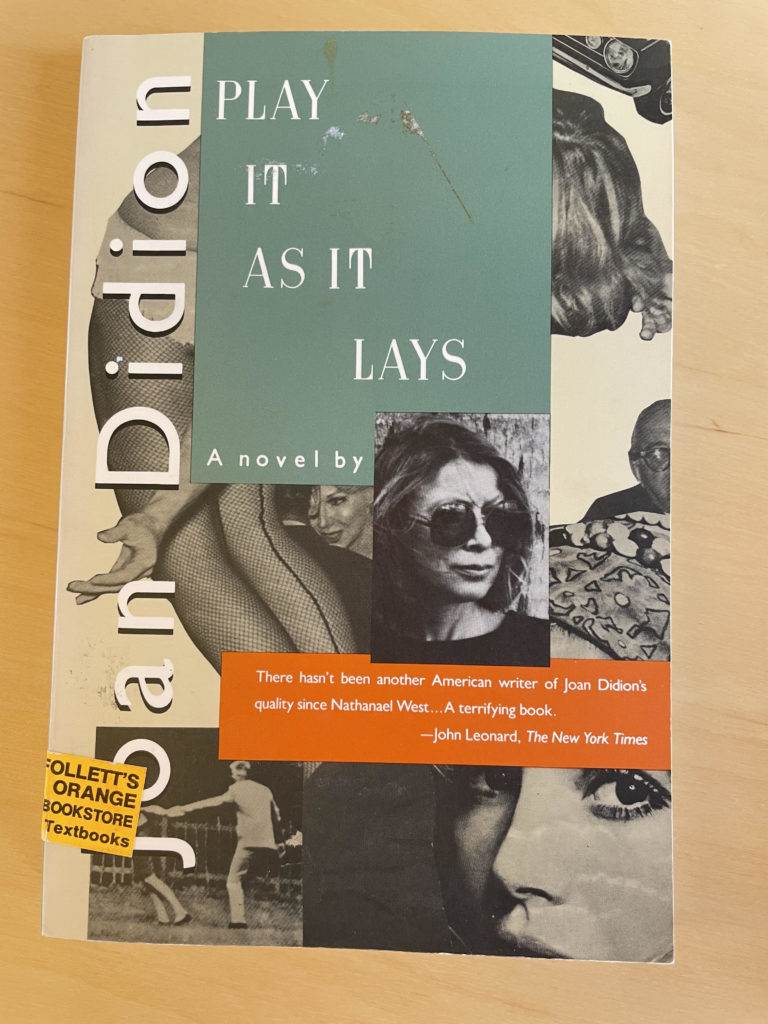

In this episode, we explore the breadth of opportunities that exist for the independent editor by talking our way through a project’s life cycle, covering many of the classic services that can be offered, including: coaching, developmental editing, ghostwriting, cowriting, line editing and ongoing assistance, copy editing, marketplace assistance (for both traditional and self-publishing) and publication support. But what you can do doesn’t stop there; we also discuss the endless possibilities for writers to turn whatever they are good at and like doing involving the written word into an income stream, and the importance of that very diversification.

You cannot be an independent editor without having clients. And so today, we talk about how to source them. They’re out there; it’s up to you to connect with them and sell your services with confidence. Believing that, earnestly networking, and accepting both when leads pan into something great and when they go nowhere are all essential parts of the equation. Which, of course, means you need to be comfortable hearing “no.” Are you ready?

When people search you out, what do they find? Are you their person? Your editorial platform is what determines this answer. All parts of your online presence work together to establish your credibility, express your personality, and show your engagement, but the crown jewel of it all is your website. In this episode, we cover both the general guiding principles and the specific building blocks you should consider while constructing your digital home. We also talk about social media’s role in your overall platform, as well as how to decide when the time is right to launch and invest in your editing website.