Yeah, we got one, too.

Stuff We Love: Demos

For a good solid year of my tour, I opened up a session on The Book Architecture Method by playing two clips from the Beatles’ song “Sexy Sadie” in succession. The first 0:46 was basically just John playing some dusky chords into a two track recorder in India. Then I played the first minute of the finished version and we talked about how George changed the lyrics to make them less of a direct attack on his guru at the time, Paul brought some bright piano chords right off the top followed by Ringo’s shuffling drumming, and they all contributed sarcastic La-la-la-la’s in the background.

The Beatles – SexySadie from Stuart Horwitz on Vimeo.

If someone walked in late, looking confused, I asked them, Are you here for the class on the White Album? My point was to show the distance traveled between the initial, halting idea for a song and the polished and produced version. We hear the latter and we thing: I could never do that… We hear the former and we think: Interesting.

It’s the same across genres and media. It’s one thing to examine a smudged charcoal landscape sketch of Van Gogh’s and quite another to be engulfed by the final days intensity of “Wheatfield and Crows.” We get confused. Confused that art isn’t made, by somebody, over a succession of drafts, each improving, if not entirely, on the version that came before it.

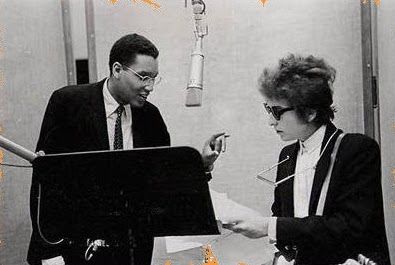

And that’s why some Stuff We Love are demos. I recently treated myself to a box set of Bob Dylan’s studio recordings from 1965-1966. It contained the finished songs from this era, which I had heard a hundred times each. There were multiple master takes so I could listen to just the piano and the bass on “Like a Rolling Stone.” But there were also a series of screw-ups and false starts, experiments, arguments, breakthroughs and new directions until some of these famous songs were codified.

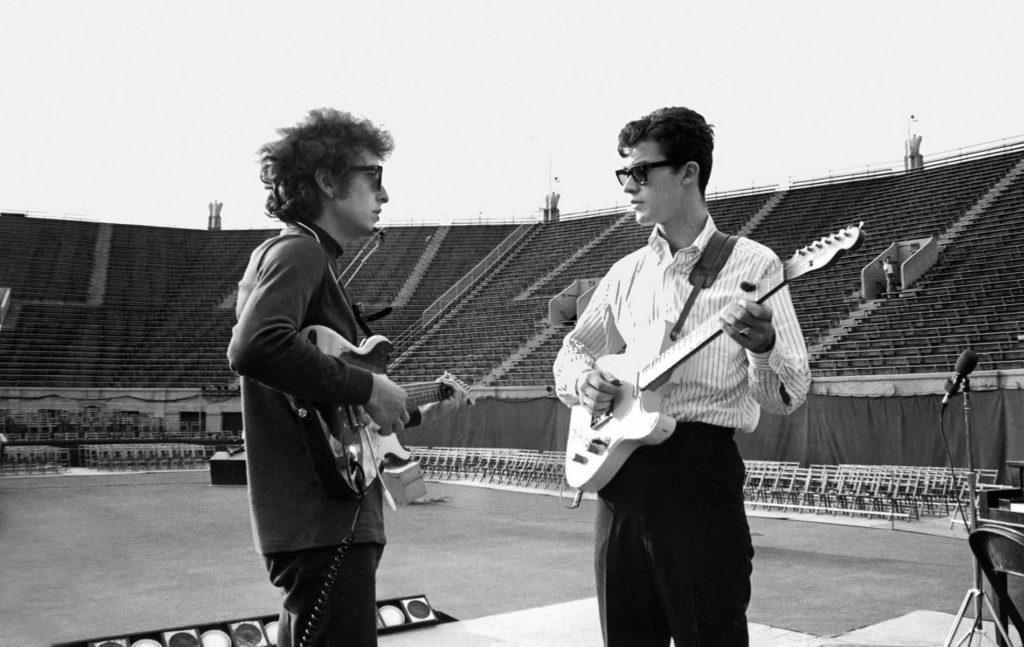

I love hearing the banter between Dylan and his bandmates, such as lead guitarist Robbie Robertson soon to be of The Band. Among the 25 takes of “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” you can hear the following exchanges:

Dylan: “Can you do that, Robbie? But I don’t mean just, I don’t just mean that. Can you do anything else? But not that. Some kind of a… no, no, no. Yeah, I do want it, but not so specific.”

*

Dylan: “I don’t think that’s the right way… do you think so?”

*

Robbie: “I’m going to modify it a little bit. To make it blend with what he’s doing.”

Dylan: “Sure! Tell me what you mean…”

I don’t know what Dylan means when he complains to Rick Danko, “No! I don’t like that bass run. That’s… that’s modal.” I’m not even sure he does. These tapes communicate being in the wilderness with only a small spark of an idea, and tending that flame so it can get air under sheltered conditions until it begins to burn on its own.

And that’s why we recommend looking for demos—translated to whatever art and taste suits you—when you need to be reminded of not just your humanity but the humanity of the artists you admire. Their experience of being lost, then gradually found, through a combination of curiosity and faith, looks like something we could call perseverance—if it wasn’t fueled at least as much by residing in the delight of creation.

I LOVE this! I am not a musician, but songwriting fascinates me. I have Jeff Tweedy’s book, HOW TO WRITE ONE SONG, on hold at the library. Excellent advice on looking up demos. I’m going to do that right now! Thank you!

So cool, Jennifer! Let us know how that is? And I can totally feel the value in writing one song, at a time, and getting it right as it seems like the title implies.

This is so true. As I write I move through many mood swings, times when I am on fire with an idea, times when I’m frustrated that the idea isn’t coming across the way I want, times when I’m sure it never will and times when all of a sudden it clicks and I love it again. It’s hard to identify those stages in the final work of other artists, and reading the books I love can make me doubt my ability to achieve something worthwhile. It’s good to be reminded that creating art requires a lot of trial and error and that even the greats go through that process.

It is hard to add much to this except, thank you! Mood swings are an occupational hazard indeed. Writers especially, but people in general, benefit from distinguishing the reactive from the proactive where their ideas are concerned. What started the chain? Was it a negative emotion. It probably won’t lead to much good. Was it a positive emotion? Where did that lead? Follow it!