We’ve curated our best editorial secrets and industry insights into a series of articles. They range from getting started through staying on track and grasping the publishing business. Put those fuzzy slippers on your feet, pull up a cushy armchair, and enjoy.

The Five Definitions of Scene

Finish Your Book in Three Drafts (3D), the third book in the Book Architecture trilogy, came accompanied by a wealth of writing know-how in the form of 9 bonus PDFs. We are opening up the vault for the first time and publishing them here: one blog at a time. Behold, PDF #1.

What’s the big deal about scene? Well, as a group of self-contained passages within your narrative, they are nothing less than the building blocks of your work. Finding the places where your scenes break and separating them into discrete units can help you move scenes around, divide and combine them, and eliminate them when necessary.

The most commonly heard expression in writing circles is probably “Show, don’t tell,” which means you must put us in the scene. Don’t tell us about it, don’t tell us that it happened, don’t tell us that your characters—or you as the narrator—had a certain set of feelings about it; make it happen for us as readers, as viewers.

From this we get the first definition of scene:

#1. A scene is where something happens.

If you are working in non-fiction, consider a scene to be the material that is grouped under a subhead where you have demonstrated your point, which is the same thing as making things happen. Now that you have introduced new material into the discourse, the discourse has shifted—which is what our second definition of scene is getting at:

#2. A scene is where because something happens, something changes.

These first two definitions are the only ones mentioned in Finish Your Book in Three Drafts (3D). Ro$hi and Biz fight; as a result, their dynamic changes: Ro$hi has increased respect for Biz, and Biz becomes willing to listen, at least for a little while.

As I said above, a scene is the basic measuring unit by which you will construct your manuscript. Once you have identified these units, you can determine if each scene is weak or strong, a hopeless aside, or the climactic scene, in large part by whether or not any given scene belongs to a recognizable series.

#3. A scene has to be capable of series.

You would be surprised by the number of scenes that are written which contain nothing that is repeated elsewhere—not the characters, not the place, not the ideas. Readers have a limited ability to track information, so unless you are intentionally presenting a red herring, what are these one-iteration series doing, just hanging out? The vibrant cafe owner with caustic wit but a heart of gold: Where did he go? That cabin that seemed so mysterious: How come we never went back there?

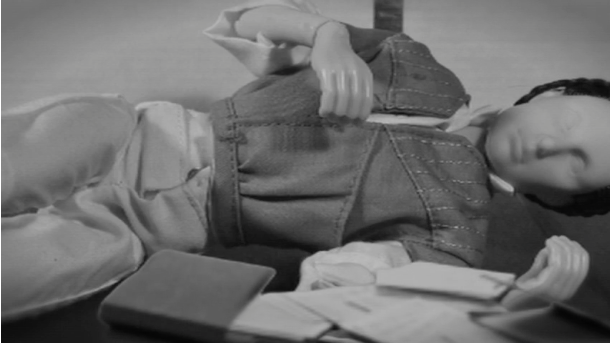

One of the series in 3D is Biz’s manuscript, that blue folder containing her sheaf of papers we first see clutched in her hand on the train. In this scene, something happens: the pencil train hits the jersey barrier of writer’s block. And because something happens, something changes: Her manuscript explodes, papers fly everywhere (just before she decides to “put the middle at the beginning, to make it more interesting”).

Later, we see the manuscript with some pages spread out as Biz writes her messy draft; we see Ro$hi take it away from her when she brainstorms her scenes from memory. Then we don’t see it much more… but we remember it, so that it strikes a chord in us when it reappears in her hands as she heads off to seek her publication fortune in the city. By the end, this object, her manuscript tucked inside its blue folder and held to her chest, has become a symbol of Biz’s finished work—or even her career as a writer. A series becomes animated (no pun intended) through scenes like these; if a scene doesn’t have any series to embody, it will likely feel flat and lifeless.

If you take all of your series and braid them together as strands, you get a strong rope, which is your theme. Because your theme is strengthened by each and every one of your series threads, which, in turn, spool out of your scenes, it makes sense that,

#4. A scene has to be in the service of the one central theme.

If all of your scenes serve the one central theme, you almost can’t miss at that point. But if you do have a scene that is not related to the one thing your book is about (because your book can only be about one thing), it has to be expandable, or it is expendable.

Finally, the fifth definition of scene is this:

#5. A scene has to have “it.”

That’s it; just “it.” I, for one, don’t think we should be above talking about things in this way. Each scene must carry with it a sense of excitement, for both the writer and the reader. A bad or forgotten scene that you decide to keep while putting together your pro- visional scenic order might have “it.” That might be why you haven’t dropped it yet. You may not know what “it” is, but you can still detect it; it resonates; you can’t quite shake it. This scene has “it”—not that it’s perfect.

Not only should we not be above talking in ways like this, sometimes I think the situation demands it. The scene where Ro$hi and Biz fight met the “it” definition for me. We almost didn’t do the scene; Ro$hi doesn’t bend that way, so that’s actually a stunt double in the video. But, if you’re going to have a character named Ro$hi—Japanese for “Zen master”—and you’re going to voice that character, I thought it would also be important that he get kneed in the nuts.