We’ve curated our best editorial secrets and industry insights into a series of articles. They range from getting started through staying on track and grasping the publishing business. Put those fuzzy slippers on your feet, pull up a cushy armchair, and enjoy.

Fifteen (More) Examples of Series

Finish Your Book in Three Drafts (3D), the third book in the Book Architecture trilogy, came accompanied by a wealth of writing know-how in the form of 9 bonus PDFs. We are opening up the vault for the first time and publishing them here: one blog at a time. Behold, PDF #3.

The more series you expose yourself to, the more easily you will recognize series in your own work. As you identify your series, I suggest you give each one a name and then assign it a type: object, person, place, phrase, or relationship.

After you have collected all of the iterations of a particular series, you can describe the repetitions and variations which it undergoes in a single sentence and identify the question that the series asks and eventually answers.

Series work goes on everywhere, from children’s books to classic literature, from modern fantasy to film. In the fifteen examples that follow (source materials are noted within each entry with a bibliographic record at the end), we will look at:

- how an object becomes a symbol,

- how a person becomes a character,

- how a place becomes a setting,

- how a phrase becomes a philosophy, and

- how a shifting relationship becomes a dynamic.

We won’t talk a lot about events, because these are all events. Think about that, plot people.

How an Object Becomes a Symbol

#1. Corduroy’s Missing Button. This series defines the nature of the quest the teddy bear will go on in the children’s book Corduroy. Corduroy’s missing button initiates the story’s action: Corduroy goes looking for his button. It then precipitates the turning point: Corduroy tries to pull a button o a mattress, slips, and breaks a oor lamp, thereby alerting the security guard, who returns him to his floor. The button also signals the story’s ending, when Lisa sews it back on Corduroy’s overalls while speaking about unconditional love.

#2. The T. J. Eckleburg Billboard. In The Great Gatsby, the billboard of the long-retired oculist Doctor T. J. Eckleburg presides over the stop on the train line between New York City and West Egg and East Egg. Nick narrates:

The eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high. They look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose. Evidently some wild wag of an oculist set them there to fatten his practice in the borough of Queens, and then sank down himself into eternal blindness, or forgot them and moved away… (p.24)

When the garage attendant, Wilson, has confirmed for himself that his wife, Myrtle, has been cheating on him with someone whom he doesn’t yet know, he sees something different in those eyes.

“I spoke to her,” he muttered, after a long silence. “I told her she might fool me but she couldn’t fool God. I took her to the window”—with an effort he got up and walked to the rear window and leaned with his face pressed against it—“and I said ‘God knows what you’ve been doing, everything you’ve been doing. You may fool me, but you can’t fool God!’” (p.159)

Michaelis, a local businessman, is standing behind Wilson and sees with some shock that Wilson is:

…looking at the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg, which had just emerged, pale and enormous, from the dissolving night.

“God sees everything,” repeated Wilson.

“That’s an advertisement,” Michaelis assured him. (p.160)

As an object series, the T. J. Eckleburg sign becomes a proxy for nothing short of a character’s religious understanding: Nick is an agnostic, Wilson a devout believer, Michaelis a disbelieving pragmatist.

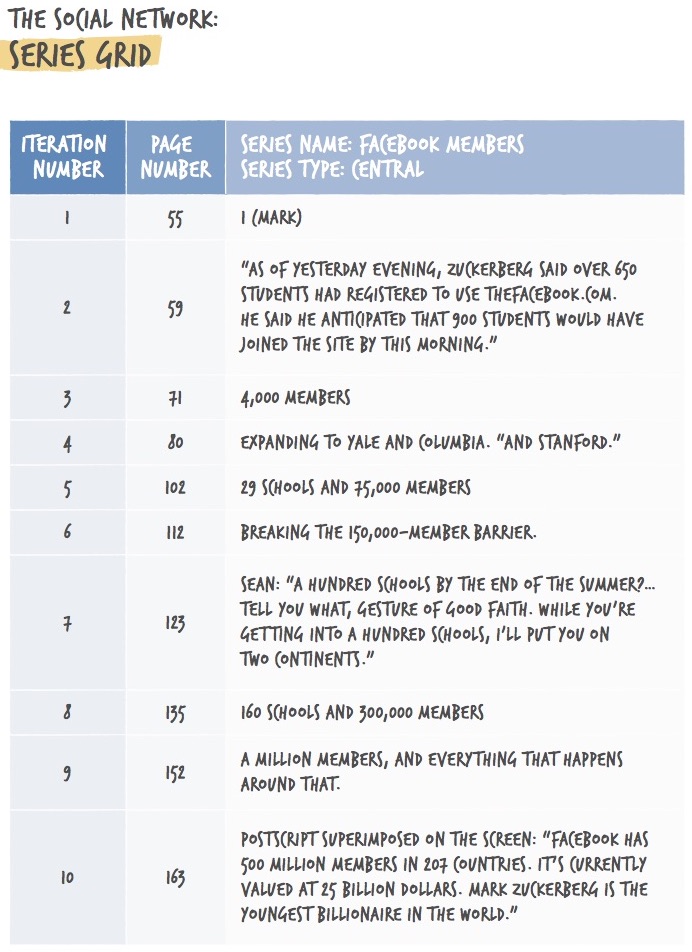

#3. The Number of Members Facebook Has. In the film The Social Network, the founding and exponential growth of Facebook is shown in terms of the number of its members, the number of schools where it is popular, and eventually, the number of countries where it is available.

Here is a series grid that shows not only the repetitions but also the variations in the Facebook Members series. Variations are crucial so that the story feels dynamic instead of cookie-cutter. We touched on Facebook’s number of members, colleges, and countries, but how about adding in a few more variants: the number of continents, who’s delivering the news about the most recent growth spurt, whether that news is delivered by a character or is visually represented, whether it is aspirational or actual, and whether or not it means anything at all in the big scheme of life.

The Facebook Members series does a good job of helping us keep track of our progress through the film. It communicates the emotional tone of the moment, and it lets us build to the scene of the “Millionth Member Party” for the film’s climax. It also lets us know what’s at stake; as one of the taglines for the film reads, “You can’t get to 500 million friends without making a few enemies.”

How a Person Becomes a Character

#4. Cameron Winklevoss, Gentleman of Harvard. Sticking with The Social Network, Cameron Winklevoss is one of two twins who row crew for Harvard—the “Winklevei,” as Mark refers to them together. These brothers live in the upper echelons of society and epitomize everything Mark wants. Mark allegedly steals their idea for a website, which results in the founding of Facebook. But Cameron doesn’t want to sue Mark until all other avenues have been exhausted, believing that that is not what a Gentleman of Harvard does. The Gentleman of Harvard series ends 80 percent of the way through the film when Cameron changes his mind: “Screw it. Let’s gut the freakin’ nerd.”

#5. Yossarian’s Naked Series. In Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22, the Naked series begins when the main character, Yossarian, is treating Snowden’s eventually fatal wound; Yossarian strips down to help the tail-gunner, who keeps complaining, “I’m cold.”

But then Yossarian leaves his clothes off. He goes to Snowden’s funeral naked and escapes notice by climbing a nearby tree. Yossarian is still naked in the third iteration of the series when he lines up to get his medal for the Ferrara mission. His superiors try to explain to the general that a man was killed in Yossarian’s plane over Avignon the previous week and had bled all over him, and that Yossarian is naked because his uniform hasn’t come back from the laundry yet, that his other uniforms are in the laundry, and so is all his underwear.

“That sounds like a lot of crap to me,” General Dreedle declared.

“It is a lot of crap, sir,” Yossarian said. (p. 218)

The Naked series shows us a man at his breaking point better than a long discussion of a breaking point ever could.

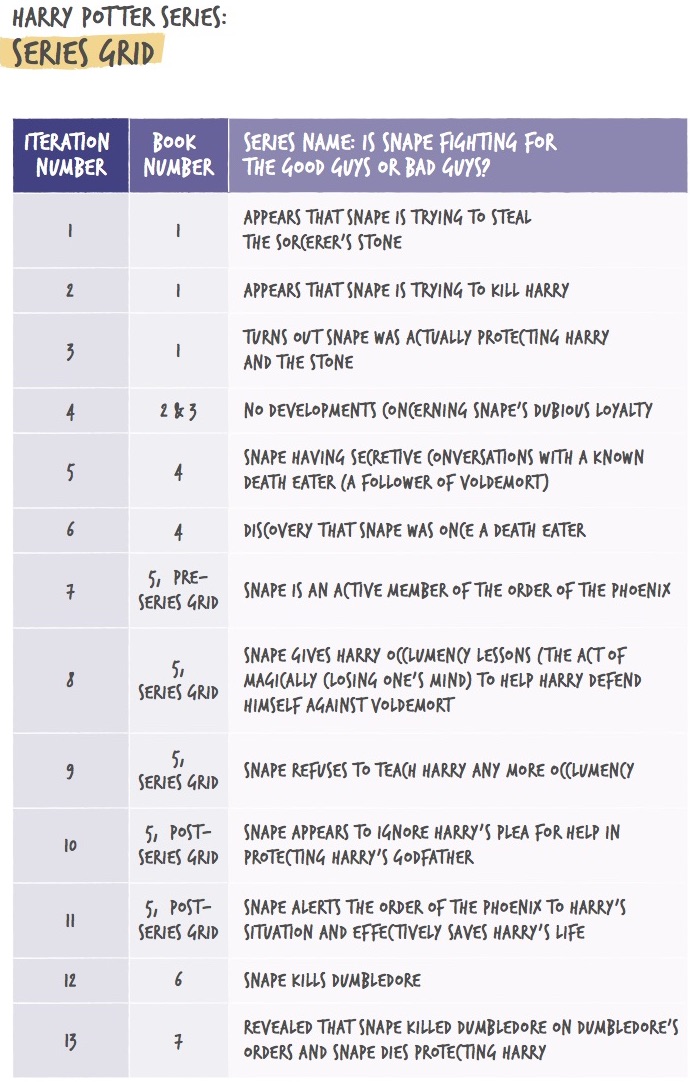

#6. Is Snape Fighting for the Good Guys or the Bad Guys? This is such a complex series that it actually takes place over the course of all seven Harry Potter books in J.K. Rowling’s series (conventional definition of series). In book five, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix—the one that my co-author, C.S. Plocher, and I studied in a chapter of Book Architecture (BA) —we finally get a glimpse at the suspicious Professor Snape’s past and a partial explanation as to why Snape seems to have such an ingrained hatred for Harry, on account of Harry’s father. Despite these developments in book five, this series pretty much stays consistent throughout all seven books, revolving around its main question: Is Snape fighting for the good guys or bad guys?

C.S. put together this series grid to show the repetitions and variations that this series undergoes over the course of the entire multi-volume narrative—which is a lot to keep track of and why a series grid is a great idea, so that you can stay ahead of the game.

How a Place Becomes a Setting

#7. The Weather Series in “The Ugly Duckling.” If you don’t know this story, you can get the gist just by following the iterations of the Weather series. In the first two, the innocence that accompanies newborn animals is reflected in the loveliness and gloriousness of the environment. The downturn in the events that affect the “ugly duckling” is mirrored in the deterioration of the next three iterations in the Weather series: it starts as a fierce wind, which turns into the kind of sheer cold that makes one shiver, and then finally the duckling becomes so weary he is frozen fast in ice.

You may believe that influencing the reader with such effects is manipulative—yet it is exactly these parallels that enrich the texture of a narrative, similar to the physiological effect of an evocative musical score in a film. We can feel the story at a sensual level, and when the weather improves in the last two iterations, it signals to us a change in the duckling’s fate and the happy ending that will follow (Hint: He’s a swan).

#8. Hall of Prophecy. For almost all of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, the true nature of the Hall of Prophecy series is a mystery to both Harry and us. By the end of the novel, however, the series ends up being the most important one in the book—and arguably all of the Harry Potter books—as it finally reveals the inevitable outcome in the war between Harry and Voldemort.

Right from the beginning, Harry dreams over and over again of a locked door. He doesn’t know why he’s having these dreams or even what these dreams are about. Then, almost exactly halfway through the narrative, Harry has a dream that Mr. Weasley, who is sleeping in front of this locked door, gets attacked by a giant snake, and the dream turns out to be true. Soon after, Harry realizes that the door he’s been dreaming about leads to the Department of Mysteries (although he’s still unaware of the Hall of Prophecy inside of it). Harry is now aware that he’s dreaming of a real place with real dangers, and he wants to know more—even though everyone around him is urging him to close his mind to it. The dreams continue without much change until 80 percent of the way through the novel, when Harry has a dream that Voldemort is in the Hall of Prophecy and is torturing Sirius, Harry’s beloved godfather.

Harry races to the Hall of Prophecy, where he discovers that Voldemort has tricked him into coming. After a battle between the good guys and bad guys, Dumbledore finally reveals the prophecy and explains to Harry why Voldemort will never stop hunting him down. Although the Hall of Prophecy is “only” a series about setting, Rowling turns it into the reason and motivation for Harry’s actions throughout the remaining two Harry Potter books.

#9. Gregor’s Bedroom. In Kafka’s novella The Metamorphosis, Gregor, the traveling salesman, wakes up one day to find he has been transformed into a giant dung beetle. He leaves his room only once more in his life. The repetitions and variations of the Gregor’s Bedroom series include Gregor trying to get out, the general manager from his offce trying to get in, Gregor being chased back inside the one time he gets out, the door being locked from the outside, and his sister, Grete, trying to get in to rearrange the furniture—before she is rebuffed. The next time Gregor leaves his bedroom is after he dies, and the charwoman reports to the rest of his family that “there’s no need for you to go worrying about how to get rid of that mess in there. It’s already taken care of.” (p.116)

How a Phrase Becomes a Philosophy

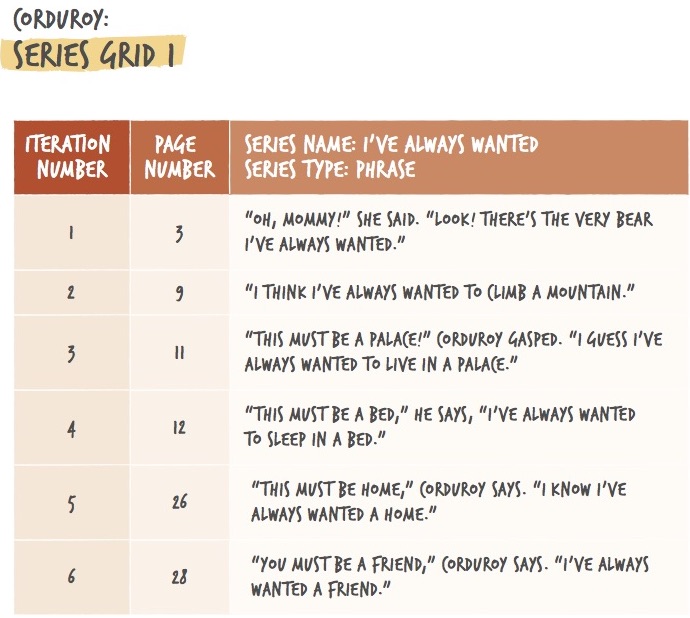

#10. “I’ve Always Wanted.” In the story Corduroy, the lead bear reflects on the things he (thinks he) has always wanted no less than six times in a 28-page children’s book.

When you start trying to find your series, all you have to remember is repetition and variation. What do you find repeated? The I’ve Always Wanted series jumps out at us through its sheer frequency. When we look closer, however, at not only the repetitions but also the variations of this particular narrative element, we see that the philosophy of Corduroy is communicated through the use of this phrase series.

If we read the book closely (or for the tenth time to an interested young party), we see that we go from “I think I’ve always wanted to climb a mountain” and “I guess I’ve always wanted to live in a palace” to “I know I’ve always wanted a home . . . and a friend” (italics mine). These repetitions and variations create meaning; if we had to define the theme of Corduroy now based on the direction of this series, I guess we could say that it’s actually an anti-materialist screed about what’s really important in this life.

#11. The Q & A Series. In the film Slumdog Millionaire, we meet Jamal, a young man from the slums of India who works a menial job

transporting tea to workers at a telemarketing center. Jamal ends up on the Indian version of the television game show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” The progression of questions Jamal is asked during the quiz show, the ten iterations of the Q & A series, corresponds to the increasing value of the question asked.

The questions go in chronological order (see PDF #5), which helps us keep track of where we are in the film—how close we are to the end, basically, since Jamal keeps winning. The iterations are also fairly evenly spaced out, as you can see from the scene number (out of 197) in the grid below where the iteration appears.

#12. Is Mark an Asshole? Mark is Mark Zuckerberg, the genius but socially inept Harvard student behind the founding of the now mega-social media site Facebook in The Social Network. His girlfriend at the beginning of the film is Erica Albright, a student who attends Boston University (BU). In the first scene, they break up, and Erica offers Mark this clarification:

ERICA: You are probably going to be a very successful computer person. But you’re going to go through life thinking that girls don’t like you because you’re a nerd. And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole. (p. 10)

In the very last scene—nearly two hours later in the film—we get the second and only other iteration of this series. The scene involves Marylin, the second-year junior associate who advises Mark to settle out of court on both of the lawsuits that resulted from the explosive success of Facebook. She tells him:

MARYLIN: You’re not an asshole, Mark. You’re just trying so hard to be. (p. 163)

The second iteration in this series is more than 150 pages later in the screenplay (or 110 minutes of running time in a 120-minute movie), but it registers just as clearly as if the first iteration had been only a few pages before. There is no formula that I know of that teaches you to bookend two powerful iterations of a series this way, but it works for this film.

How a Relationship Becomes a Dynamic

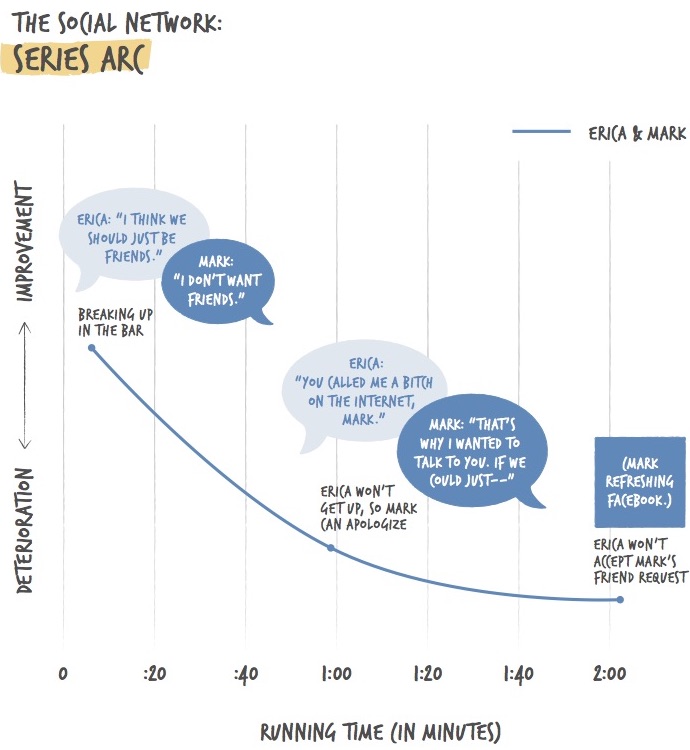

#13. Erica & Mark. Erica (Albright) and Mark (Zuckerberg) are the ill-fated couple in The Social Network referred to in the previous entry. The very first scene of the film has them breaking up in a bar.

ERICA: I think we should just be friends.

MARK: I don’t want friends.

ERICA: I was being polite, I have no intention of being friends with you. (p. 9)

Erica then disappears for half the movie. When they run into each other at a club, Mark tries to apologize but Erica isn’t having it. In fact, she won’t even get up from the table where she is sitting with her friends to talk with him.

ERICA: You called me a bitch on the internet, Mark.

MARK: That’s why I wanted to talk to you. If we could just –

ERICA: On the internet. (p.78)

At the end of the film, even though Mark has become the youngest billionaire in the world, Erica—who is on Facebook—won’t accept his friend request on Facebook. As the Beatles sing “Baby You’re a Rich Man,” Mark continually refreshes his computer screen, but each time he comes up empty.

#14. Pain and Aggression in “The Ugly Duckling.” In “The Ugly Duckling,” a Pain and Aggression series marks the main character’s interactions with pretty much everyone he comes across. They either want to kick him in the water, fly at him and bite him in the neck, push him around, or peck at him. In these four iterations of the Pain and Aggression series, nothing of importance actually changes. Instead it is an example of how repetition without variation builds the internal pressure of the story, leading the reader to seek some narrative resolution. The relentlessness of the presentation leads us to the inevitable conclusion that suffering pain and inciting the aggression of others is the natural result of the ugly duckling’s existence.

Once the repetitions have been clearly established in this way, the variations will have an even more powerful impact on the reader. The next variation occurs when the duckling is taken into the home of a peasant couple; when the children try to play with him,“the duckling thought they were going to ill-use him, rushed in his fright into the milk pan, and the milk spurted out all over the room.” This is just like life; the ugly duckling has seen this scenario unfold one too many times. He now assumes that every creature he meets will want to attack him. My wife, who is a psychologist, would say that the ugly duckling had posttraumatic stress disorder, including the characteristics of “persistent re-experiencing of the traumatic event” and “avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma.” The important thing for us to consider here is the twist in this series. Andersen knew what all good storytellers know—that each time an iteration is presented, there is an opportunity to evolve the series to which it belongs.

#15. Gregor and Grete. In the Gregor and Grete series in The Metamorphosis, we see Gregor’s sister, Grete, going through a change and thus becoming a round character. After Gregor first turns into a monstrous insect, Grete is the only one to approach his condition with a lament. When Gregor can’t seem to explain his predicament suitably to his general manager, he wishes Grete were there because she is clever and could have talked the man out of his fear.

She is the only family member who cares for Gregor, bringing him milk, which used to be his favorite drink, except now that he’s an insect, he prefers two-day-old milk and old cheese, so she brings him that instead. She even moves the armchair back to where she knows he likes it after she is done cleaning his room.

She’s really doing the best she can, until Gregor interferes with her plan to adjust the contents of his room. Gregor’s mother, who hasn’t seen him in weeks, is part of the moving team. When Gregor bursts out of hiding, his mother faints, which enrages Grete. She then raises her fist at Gregor with “a threatening glower.” Her gesture of violence, along with shouting his name—the first time she has addressed him directly since his metamorphosis—shows her allegiance transferring to the side of their father—which, if you haven’t read the novella, is not a good place to be. Remember, not all series have to improve. Even though “Americans love a tragedy with a happy ending,” according to William Dean Howells, some series can deteriorate until the point of tragedy and then stop—that’s it. Then it’s up to us, as the reader, to make some sense out of that, so that the net effect is not tragic.